Modernisation

Indian planners have always acknowledged the importance of science and technology to the advancement of their nation. The use of advanced technology and science in production raises output levels and, over time, quickens the rate of economic growth. When India gained its independence, it lacked a great deal of technical expertise.

Additionally, the technology employed in actual production was typically antiquated. The methods of production used in agriculture were almost always centuries old. The country’s reliance on technology imports was significant when the planned development era began. From the outset, the planners emphasized the significance of research and development (R&D) due to the problems that frequently result from a nation’s reliance on foreign technology.

The Sixth Plan was the first to specifically state modernization as a goal. The planners defined modernization broadly and gave it a wide definition. “The term modernization connotes a variety of structural and institutional changes in the framework of economic activity,” the Plan document said.

In order to convert “a feudal and colonial economy into a modern and independent economy,” it thus implied a “shift in the sectoral composition of production, diversification of activities, an advancement of technology, and institutional innovations.”

If the idea of modernization is accepted, then it must also be acknowledged that India made progress toward modernization throughout the planning period.

Modernization is a complex idea that includes how economies, societies, and cultures change in response to new developments in technology, shift patterns in societal norms, and shifting international trends. Basically, modernization is the process of replacing outdated or pre-industrial ways of living with more advanced and effective systems of governance and organization.

This process entails adopting modern systems, technologies, and values with the goals of raising productivity, promoting socio – economic growth, and raising living standards. Economic development is one of the main characteristics of modernization. Modernization initiatives must include urbanisation, industrialisation, and the growth of trade and commerce.

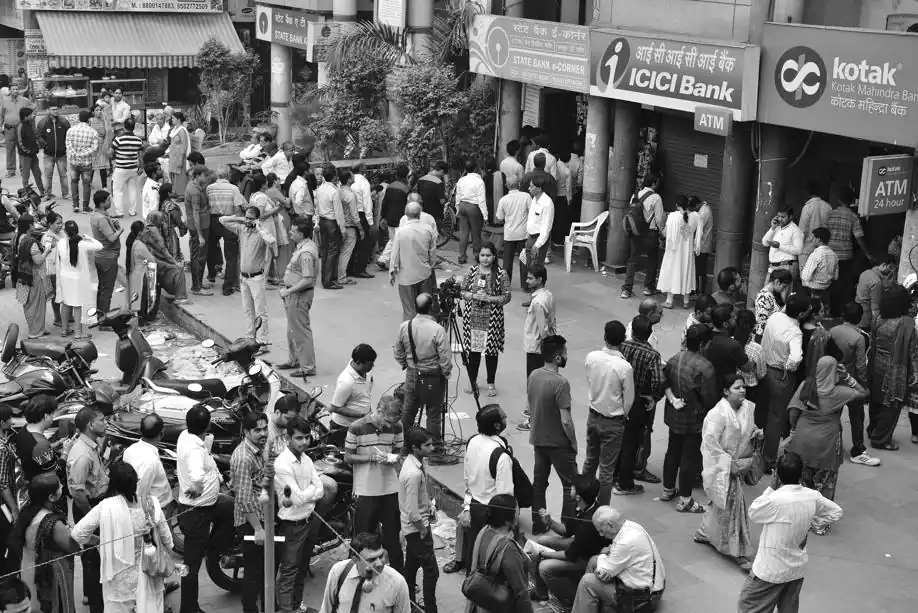

As economies transition from agricultural to industrial and service-oriented, they experience structural changes. Usually, this shift involves the industrialization of manufacturing and the mechanisation of agriculture, the establishment of manufacturing industries, and the growth of service sectors such as finance, healthcare, and information technology.

Throughout the course of 39 years of planning, the makeup of the national income has gradually shifted. Manufacturing, mining, construction, and productive infrastructure accounted for roughly 20% of the total in the early 1950s and 30% of the total in the late 1980s.

Remarkable progress has been made in the industrial sector in terms of diversification. India’s technical know-how capabilities today surpass those of the early 1950s by a wide margin. Even within the institutional framework, the accomplishments of this nation are noteworthy.

The establishment of development banks aimed at promoting industry and agriculture, the creation of innovative Regional Rural Banks, and the expansion of co-operative credit into the most remote regions of the nation have significantly changed the institutional structure of credit.

The definition of modernization was restricted in the Seventh Plan. Today’s planners define modernization as essentially referring to technological advancements. In terms of agriculture, this means using more HYV seeds and fertilizers, expanding irrigation systems, managing water better, adapting energy consumption patterns, and increasing mechanisation. With time, it is hoped that all of these actions will bring the green revolution to new regions.

Although there have been many significant technological advancements in industry, the most significant ones come from three main sources: (a) the use of computers and electronics in production processes; (b) increases in the fuel efficiency of drive systems and other industrial equipment; and (c) the use of new materials.

The Sixth Plan era marked the start of implementing these economic reforms. There is no denying that these actions will boost productivity and followed by a rapid economic expansion. However, uncontrolled modernization carries a risk. Many industrial workers may lose their jobs as a result of steadily rising automation in industries in a labor surplus economy like the one we have in this country.

The objectives of Economic planning

The primary goals of economic planning, as highlighted in different plans, cannot be achieved at the same time. Progress is expected to be attained in all directions, frequently dismissing the compatibility between different objectives. But past experience has not lived up to these expectations.

The goals of reducing income inequality and achieving rapid economic growth appear to be at odds in India’s mixed economy, and the planners noticeable lack of information of the trade-offs between them is evident. India’s developing economy differs significantly from the world of Keynes. Using different redistributive measures will increase the marginal propensity to consume in the developed West, which will grow the economy.

Increased investment will undoubtedly lead to both increased employment and general development. But the safety and effectiveness of this policy will be diminished in India. The main barrier to this nation’s development is a lack of capital.

Unlike the unemployment in the Keynesian world, the majority of unemployment in this country is structural in nature. The rate of saving is not high enough to keep up with the rate of investment needed to give everyone a job. The methods that can produce a sufficient surplus for quick economic expansion are designed to disturb the creation of new jobs, which will worsen wealth and income economic inequality.

During the process of expressing the goals of the Fourth Plan, the majority of the language made reference to the reduction of income and wealth disparities clearly and explicitly. But the Planning Commission’s disinterest in achieving this goal was kept a secret.

This can be easily and quickly analyzed based on the broad definition of the fourth plan document, which states that fiscal measures aimed at reducing income at the top levels can, to some extent, reduce income disparities. However, we believe that far more emphasis should be placed on positive steps that can be taken to improve the conditions of the poor through planned economic development.

The transfer of income through pricing, fiscal, and other policies could contribute to greater equality in a wealthy nation. In a developing nation where investments in the economy are necessary to create the foundation for future increases in consumption, any surpluses from the higher incomes of the wealthier classes cannot be mobilized to produce meaningful results.

“But a plan of development, which accepts a national minimum and aims at assuring the same to all within a shortest possible time, cannot depend entirely on a high rate of economic growth,” wrote Dandekar and Rath in criticism of the Plan’s methodological approach.

The upper middle class and wealthier segments of society gain far more from the processes of development than do the lower middle class and the poorer sections, unless there is a intentional policy in place to guarantee an equitable distribution of the benefits of development.

Hence, even a rapid growth rate that is most likely unfeasible will not be able to raise the bottom of society to the ideal level in the near future. This is a warning, not a plea for slower growth, that intentional policies to guarantee the fair distribution of development’s benefits must still be implemented in addition to expanding GDP.

When Mahbub-ul-Haq states briefly that “we were taught to take care of our GNP as this will take care of poverty, it seems that he speaks for a great number of economists.” Let us reverse this trend and address poverty, which will benefit the GNP. The Fifth Plan also emphasized the importance of eliminating poverty.

However, Suresh D. Tendulkar explains how superficial the planners’ commitment was by saying, “It is found that the basic statement of the social objective is a non-statement.” The discussion of the ‘policy-frame’ demonstrates a preference for abstract logic over operationality. The programs for the removal of poverty are unclear in terms of their quantitative effects in the achievement of the social objective.

To summarize, modernization in India is a complex and multifaceted process that includes economic, social, technological, and environmental aspects. While India has made significant progress in modernizing its economy, infrastructure, and society, there are still challenges to addressing socioeconomic disparities, environmental degradation, and ensuring inclusive and sustainable development for all citizens.

Moving forward, India’s modernization journey will necessitate ongoing efforts to capitalize on the opportunities provided by globalization and technological advancements while addressing the socioeconomic and environmental challenges of the twenty-first century.

To summarize, modernization in India is a complex and multifaceted process that includes economic, social, technological, and environmental aspects. While India has made significant progress in modernizing its economy, infrastructure, and society, there are still challenges to addressing socioeconomic disparities, environmental degradation, and ensuring inclusive and sustainable development for all citizens.

Moving forward, India’s modernization journey will necessitate ongoing efforts to capitalize on the opportunities provided by globalization and technological advancements while addressing the socioeconomic and environmental challenges of the twenty-first century.